Katrina Relief Work Report

My son, Forrest, and I landed at Gulfport/Biloxi Regional Airport after a day of travel to find the entire airport a construction zone. Ten months before Hurricane Katrina had ripped the entire front of the terminal off and the result looked as though the place was being reconstructed from the ground up. We came to volunteer for a week with HandsOn Gulf Coast, a relief arm of the HandsOn Network of volunteer groups that has been contributing to the rebuilding of East Biloxi for the last ten months.

We arrived to find HandsOn occupying the building behind a church that had been donated for their use. It included a commercial kitchen, central dining/meeting room, sleeping loft with bunk beds, and plenty of tent space out back. Between fifty and two hundred volunteers occupy this camp. Outdoor showers, laundry, and tool room were in an adjacent building. The completely volunteer community had formed in the wake of the hurricane and kept itself going for all these months from the work of drop-in workers just like us.

Group members had been there for various lengths of time, some for the full ten months. Those staying beyond a month or so had become "long-timers" and had taken on administrative jobs. A majority of people seemed to stay for a week or two. As Biloxi was moving from crisis management to long-term reconstruction, the HandsOn community was in the midst of a gradual shift towards a more stable a narrowly defined role in the relief effort. But the daily work assignments still varied widely, with something available for almost any ability level - gutting homes, mold remediation work, drywall work, helping at the local Humane Society and Boys and Girls Club, legal advocacy and social work, structural assessments of damaged homes - the list went on.

Arriving just at "lights out", Forrest and I got a quick walk around tour, found a pair of available bunks and sacked out in anticipation of the morning.

Wake up was at 7AM with a group breakfast and then loading vehicles with tools for the days work. Various donors, most notably The Home Depot, had contributed vehicles, trailers, tools, supplies, tents, bunks, mattresses, computers, and much more to the HandsOn effort. Forrest and I headed off with a team for our first day on an "Interiors" job involving a variety of repairs for a homeowner who had been the victim of an unscrupulous contractor.

Driving along the coast highway to the job the full impact of the storm's destruction was apparent even a year after Katrina. Biloxi, a resort community of casinos and beautiful beach coastline had lost all of its core businesses and most beautiful homes. Twenty-five foot storm surge waves, coming in repeated sets with 120 mile per hour winds had literally swept away entire hotels, casinos, mansions, apartment complexes, and strip malls into the ocean. Sand was heaped everywhere in the neighborhoods many blocks inland and the resulting debris on the beach and in the shallow water had left the beaches a hazard zone. Many tall buildings were left eerily standing on their steel supports where the first floors had been gutted by the waves.

The back bay of Biloxi had also filled with surge waters and flowed back through the city core, colliding with water off the beach into thirty foot standing waves funneled through the downtown streets, following paths of least resistance. With some imagination one could visualize the flow and direction of the confluence of water that had, in a few hours time, destroyed whole sections of the city. It was hard to resist a shudder at what had happened here and the horror that those who stayed must have experienced. Taking pictures was an exercise in capturing images of what remained. But it was the buildings that were wholly missing that compelled the most shock.

A comment I heard more than once while in Biloxi referred to the ubiquitously persistent signs for the Waffle House chain. While all the lightweight fast food and motel construction had succumbed and been obliterated by the storm, their signs, although crippled and bent had often survived to some extent. But none had faired as well as the Waffle House. The comment I heard? - "Next hurricane, I'm gonna hang onto a Waffle House sign".

We worked that day for an African American woman, Regina, whose house had had 6 feet of water in it. She was living in a FEMA trailer in her front yard. The house had escaped the kind of damage that had leveled other homes because it was made of brick. We would see this same fact repeated throughout our trip, like an echo of the Three Little Pigs story. Regina had been ripped off by a series of four unscrupulous contractors who had walked off with down payment money, stolen her extra materials, and left her with the worst drywall job on her ceilings that I have ever seen.

We spent two days doing repairs to floors and a blown out wall, mold remediation in some gutted rooms, and moving furniture. Regina was incredibly thankful, and at one point shared with us the involved saga of losing her job, caring for her mother, dealing with trying to get her medications for high blood pressure and diabetes, and the stress of being ripped off after looking desperately for help. The roadsides around Biloxi were peppered with small signs, like those real estate agents use, advertising carpentry, drywall, mold work, tree clearing, etc. It was a heyday for anyone with enough gumption to throw some tools in their truck and make a sales pitch - without any guarantee about quality or credentials. After the forth contractor Regina decided to only trust the churches and volunteer agencies for help.

After the first day Forrest began going on different crews than me. The variety of work available offered something for everyone. The second day he went to the Humane Society to help care for orphaned animals. Not only had many pets been abandoned by those fleeing the storm, but the city full of people living now in trailers could not absorb the adoption of pets that presses upon any municipality. It was a low-key day for Forrest holding kitten and puppies, getting peed and pooped on, and taking dogs for walks.

The next day Forrest went with a large crew to do archeological style salvage work at Jefferson Davis's historic mansion, Beauvoir. An article about the effort to restore this National Register Historic Site and Presidential Library is covered in an article in a recent issue of "Preservation", the magazine of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The National Trust has listed the entire Gulf Coast as one of this year's 11 most endangered places and is taking an active role in many levels of work in the region.

Beauvoir (Beautiful View) was Davis's retirement home where he wrote his memoirs. The site included the Greek Revival mansion, the archetypal style of the Gulf Coast. Nearly 300 National Register buildings were lost in the storm. Beauvoir, 12 feet above sea level, and elevated nearly 10 feet more on a raised foundation, and the survivor of 21 previous hurricanes nevertheless suffered extensive damage. The back porch collapsed, and portions of the roof and ceiling were caved in. Two smaller structures on the site were completely swept away, the Confederate museum was destroyed, and the first floor of the Presidential Library was gutted.

Forrest spent the day sifting through the collected piles of debris meticulously with screens looking for artifacts that the storm had scattered. His group found pottery shards from the collection donated by Stonewall Jackson, and buttons from Confederate uniform from the museum. So far over 3,500 artifacts have been recovered and processed in a semi trailer converted to a workroom. There they are sorted, catalogued, photographed and sent on for humidity controlled storage until it is time for them to be repaired. One thing complicating the search process was that replicas of the pottery had been available for sale in a gift shop just in front of the storage room where the real artifacts had been stored. Katrina did a thorough job of smashing and combining the two sets of china, and now the crew was picking up the pieces.

Of all the work that HandsOn has done in Biloxi it is the unglamorous and labor intensive work of mold remediation that has won the respect of other aid groups, most notably the Salvation Army which, along with Architects for Humanity is heading up a large effort to rehabilitate whole blocks of flood damaged homes. HandsON has been running scientific test studies of different systems of mold work, determining which works the best and is the most cost effective. And their crews of young able volunteers, led by highly motivational crew leaders has set a standard in the community for dedication and hard work.

For my last three days of work I joined a mold crew in a quest for the coveted Mold Bracelet. This was a simple green rubber ring inscribed with the words "HandsOn Gulf Coast - Fight Mold", and given only to those hardy volunteers who had suffered three full days in tyvek suits and 90-degree heat. Our crew leader was Nick, a young twenty-something volunteer long timer with an incredibly upbeat and motivational spirit. From the beginning HandsOn has been built by young people who took charge in a situation of chaos and little resources, stepping up and leading crews of other volunteers after only a scant week or so of experience themselves. Nick and his partner in mold crime, Paul, were on a "Mold Marathon", racking up over a dozen consecutive days of mold work, leading crews through a series of back to back jobs in an effort to stage a mass renovation effort of ten homes in a month by Architects for Humanity. This will be a pilot move leading to a 70-house effort.

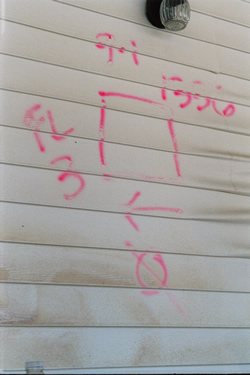

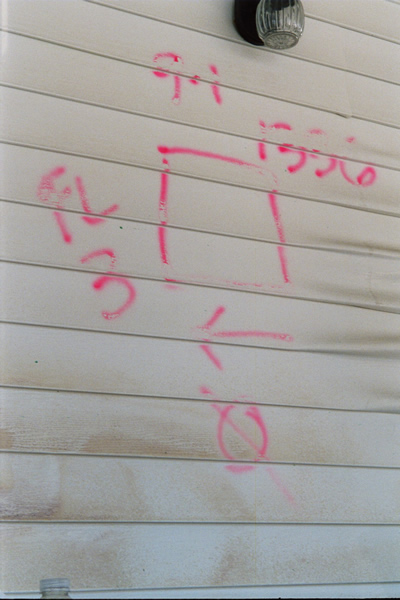

After a half day finishing a house in a predominantly Vietnamese part of town we went to the house of Tom and Sharon, an African American couple living, like everyone else, in a FEMA trailer next to what used to be their home. The house was gutted to the studs, with all the rubble, drywall, and insulation piled in the street awaiting the trash haulers. The back of the house had been recently re-roofed. The original metal roof over that portion of the house had peeled off like a lid in the storm and the attic there had been thoroughly soaked. Now facing us up in the rafters, where the temperature was a good 5 or 10 degrees hotter, was the worst mold Nick had seen yet.

For three days, which completely redefined for me the meaning of sweating, we worked in the rafters under the new roof. The process involved grinding the mold off with wire wheels mounted on angle grinders, carefully vacuuming all the dust with HEPA filter vacs, and then wiping down all surfaces with a bleach solution. The wiping process was labor intensive, but better than spraying, which had proved to reintroduce too much moisture.

For the final day Forrest joined me on the mold team. During a break Nick proposed, "what should our team name be?" And because a Neil Young classic was just coming on the radio we became the "Heart of Mold." Michelle from New Jersey pulled on her tyvek suit and mask and started up the Oompa Loompa dance on the front porch, we all put our hands in the circle together and shouted "Heart of Mold" and raced into the house to fight wood destroying organisms.

For our final day and night we took a trip into New Orleans to visit my Bellingham friend Karlina who has spent the whole ten months since Katrina working for Common Ground, a relief group servicing the lower ninth ward and St. Bernard's parish. Common Ground was born in the lower ninth ward during the chaotic days immediately following the storm as a group protecting and advocating for the rights of the most hard hit and oppressed victims of the disaster.

Karlina took us on a quick driving tour of these now famous devastated neighborhoods. As we drove down completely leveled streets which used to be lined with homes Karlina said, "Oh, this is so much better than the last time I was down here. They've really cleaned things up." Forrest and I were in disbelief. The place looked like the aftermath of war. In one place a house was on top of a car. Most homes were simply gone and the neighborhoods were almost wholly unoccupied.

About a mile south of the place where the levees broke and a twenty five foot wall of water had swept through the lower income neighborhoods was the sprawling refinery complex of Murphy Oil. Everything here had been under water for a month, and at one point one of the one-and-a-half million gallon tanks had ruptured, and the entire section of the city had been swimming in a toxic soup of oil. The solution was to repair the dikes and simply pump the gunk back over the levee into Lake Pochetrane, in a complete hands-thrown-up gesture to environmental laws.

Then, by all evidence, the "clean up" effort had consisted of pressure-washing the oil bathtub ring off the sides of the most visible buildings. A recent report I heard on NPR radio interviewed a homeowner in St. Bernard parish who had oil bubbling up out of her lawn. Driving around we saw many homes with black streaks across them at the waterline, the ground everywhere was black, and in places it was obvious that trees had simply died from the toxicity of the soil. It was common on the gulf coast that debris from house gutting and clean up efforts just had to be piled out on the street for government trucks to come by and haul it away. At one house in St. Bernard parish the homeowner had simply stripped a layer of topsoil one foot deep from his entire lot and put it on the street, in effect saying to the powers-that-be "I don't want it - you take it."

That evening Karlina showed Forrest and I a video she and a crew from Common Ground had produced about their work and the social injustice of the aftermath of Katrina. Common Ground had set up the only shelter for single women available in the city after the storm, they had gone into neighborhoods where police were threatening citizens and made "safe houses", and at schools and the yards of homes they had planted standing crops of sunflowers to suck the toxicity from the soil.

Seeing the video it became clear to me that all the skills that volunteers had brought to bear upon the situation in New Orleans had come from many years of community work back home. Common Ground, as an alternative relief agency, owed a great deal of it's effectiveness to the skills and knowledge of volunteers, like Karlina, who previous to the storm had already learned how to organize groups, run community kitchens, provide low cost health care, and advocate for minorities and oppressed populations. In this sense I could see that the real lasting story of Katrina would be the energizing and engagement of the many levels of our society where volunteerism and alternative solutions are already at play.

If there is a positive story to tell here it is the story of a social renaissance happening on the Gulf Coast. Biloxi is recovering well because the community was hit as a whole, and as a whole they are pulling together to rebuild. In New Orleans the impact was weighted towards lower income sections of the city and the balancing of social justice and recovery there is much more challenging. But the lasting effect of Katrina will ultimately be to uncover conditions of injustice and create more social equity. And in the country as a whole the message is clear - "we support each other".

The next day Forrest and I drove back to Biloxi and caught our flight home. Rising up over the city in the plane I could look down on the rooftops, a sea of blue tarps checker-boarded over the neighborhoods. Homeowners with money were well along in their reconstructions while other homes looked to have had almost no work done at all. Just that week the first jobs had opened up in town with the reopening of the casinos. Sharon, whose house I had scrapped mold from, had put on a nice dress two days before and gone off from her FEMA trailer with a huge smile for a job interview. Perhaps Regina would soon move back into her home, get her old job back, and finally have enough money for her prescriptions and to care for her mother. And the Architects for Humanity were starting up their collaboration with HandsOn to restore dozens of homes. It was hard to leave, feeling that we had done so little and had had so little time to give. But it felt good knowing that we were leaving behind a strong community of volunteers, new friends, who were there to continue the work.